An old fight in a new battlefield: college tuition.

Apparently there's some talk of differentiated tuition for some degrees at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. This gets people upset for all kinds of reasons. Let me summarize the two viewpoints underlying those reasons, using incredibly advanced tools from the core marketing class for non-business-major undergraduates, aka Marketing 101:

Viewpoint 1: Price Segmentation. Some degrees are more valuable than others to the people who get the degree; price can capture this difference in value as long as the university has some market power. Because people with STEM degrees (and some with economics and business degrees) will have on average higher lifetime earnings than those with humanities and "studies" degrees, there is a clear opportunity for this type of segmentation.

Viewpoint 2: Social Engineering. By making STEM and Econ/Business more expensive than other degrees, the UNL is incentivizing young people to go into these non-STEM degrees, wasting their time and money and creating a class of over-educated under-employable people. Universities should take into account the lifetime earnings implications of this incentive system and avoid its bad implications.

I have no problem with viewpoint 1 for a private institution, but I think that a public university like UNL should take viewpoint 2: lower the tuition for STEM and have very high tuition for the degrees with low lifetime earnings potential. (Yes, the opposite of what they're doing.)

It's a matter of social good: why waste students' time and money in these unproductive degrees? If a student has a lot of money, then by all means, let her indulge in the "college experience" for its own sake; if a student shows an outstanding ability for poetry, then she can get a scholarship or go into debt to pay the high humanities tuition. Everyone else: either learn something useful in college, get started in a craft in lieu of college (much better life than being a barista-with-college-degree), or enjoy some time off at no tuition cost.

I like art and think that our lives are enriched by the humanities (though not necessarily by what is currently studied in the Humanities Schools of universities, but that is a matter for another post). But there's a difference between something that one likes as a hobby (hiking, appreciating Japanese prints) and what one chooses as a job (decision sciences applied to marketing and strategy). My job happens to be something I'd do as a hobby, but most of my hobbies would not work as jobs.

Students who fail to identify what they are good at (their core strengths), what they do better than others (their differential advantages), and which activities will pay enough to support themselves (have high value potential) need guidance; and few messages are better understood than "this English degree is really expensive so make sure you think carefully before choosing it over a cheap one in Mechanical Engineering."

It's a rich society that can throw away its youth's time thusly.

Non-work posts by Jose Camoes Silva; repurposed in May 2019 as a blog mostly about innumeracy and related matters, though not exclusively.

Saturday, April 30, 2011

A situation in which I have to defend Gargle

I try not to judge, but ignorance and lax thinking of this magnitude is hard to ignore.

I'm far from being a Google fanboy and have in the past skewered a fanboy while reviewing his book; Google has plenty of people in public relations management, a lot of money to spend on it, and doesn't need my help; and every now and then I cringe when I hear people refer to Google's "don't be evil" slogan.

But this self-absorbed post makes me want to defend Google, for once. Here's the story as I see it, and as most people with even a passing interest in management and some minor real-world experience would probably see it:

A person was fired for indulging his personal politics at a contract site in a way that endangered the contract between his employer and the client (whose actions were legal and generous beyond the current norm).

I'll add that every company has a "class" system, using the scare quotes because the original poster chooses that word for emotional effect due to its association with reprehensible behavior (that doesn't apply here). The appropriate term is hierarchy.

Google apparently gives many fringe benefits to some contractors (red badge ones): free lunches, shuttles, access to internal talks; this is incredibly generous by common standards. But in the everyone should have everything everybody else does mindset of the original poster, the existence of different types of contractor (red vs yellow badges) is indicative of something bad.

Gee, how lucky Google was that this genius didn't learn about the discrimination in the use of the corporate jets. Imagine what his post would be like if he had learned that the interns couldn't use the company's 767 to take their friends to Bermuda.

He mentioned he was going to grad school; probably will fit in perfectly.

I'm far from being a Google fanboy and have in the past skewered a fanboy while reviewing his book; Google has plenty of people in public relations management, a lot of money to spend on it, and doesn't need my help; and every now and then I cringe when I hear people refer to Google's "don't be evil" slogan.

But this self-absorbed post makes me want to defend Google, for once. Here's the story as I see it, and as most people with even a passing interest in management and some minor real-world experience would probably see it:

A person was fired for indulging his personal politics at a contract site in a way that endangered the contract between his employer and the client (whose actions were legal and generous beyond the current norm).

I'll add that every company has a "class" system, using the scare quotes because the original poster chooses that word for emotional effect due to its association with reprehensible behavior (that doesn't apply here). The appropriate term is hierarchy.

Google apparently gives many fringe benefits to some contractors (red badge ones): free lunches, shuttles, access to internal talks; this is incredibly generous by common standards. But in the everyone should have everything everybody else does mindset of the original poster, the existence of different types of contractor (red vs yellow badges) is indicative of something bad.

Gee, how lucky Google was that this genius didn't learn about the discrimination in the use of the corporate jets. Imagine what his post would be like if he had learned that the interns couldn't use the company's 767 to take their friends to Bermuda.

He mentioned he was going to grad school; probably will fit in perfectly.

Labels:

google,

management

Saturday, April 23, 2011

The illusion of understanding cause and effect in complex systems

Also know as the "you're probably firing the wrong person" effect.

Consider the following market share evolution model (which is a very bad model for many reasons, and not one that should be considered for any practical application):

(1) $s[t+1] = 4 s[t] (1-s[t])$

where $s[t]$ is the share at a given time period and $s[t+1]$ is the share in the next period. This is a very bad model for market share evolution, but I can make up a story to back it up, like so:

"When this product's market share increases, there are two forces at work: first, there's imitation (the $s[t]$ part) from those who want to fit it; second there's exclusivity (the $1-s[t]$ part) from those who want to be different from the crowd. Combining these into an equation and adding a scaling factor for shares to be in the 0-1 interval, we get equation (1)."

In younger days I used to tell this story as the set-up and only point out the model's problems after the entire exercise. In case you've missed my mention, this is a very bad model of market share evolution. (See below.)

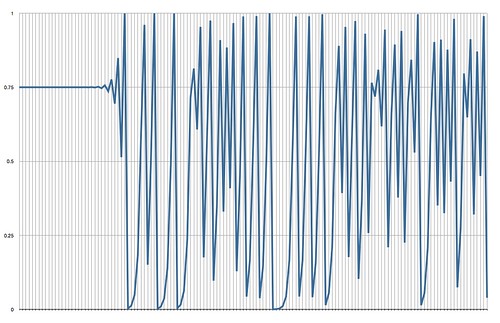

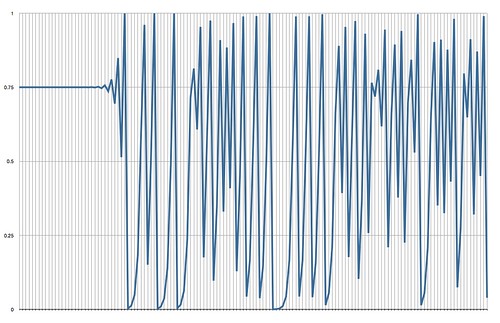

Using the model in equation (1), and starting from a market share of 75%, we notice that this is an incredibly stable market:

(2) $s[t+1] = 4 \times 0.75 \times 0.25 = 0.75$.

Now, what happens if instead of a market share of 75%, we start with a market share of 75.00000001%? Yes, a $10^{-10}$ precision error. Then the market share evolution is that of this graph (click for bigger):

The point of this graph is not to show that the model is ridiculous, though it does get that point across quickly, but rather to set up the following question:

When did things start to go wrong?

When I run this exercise, about 95% of the students think the answer is somewhere around period 30 (when the big oscillations begin). Then I ask why and they point out the oscillations. But there is no change in the system at period 30; in fact, the system, once primed with $s[1]=0.7500000001$, runs without change.

The problem starts at period 1. Not 30. And the lesson, which about 5% of the class gets right without my having to explain it, is that the fact that a change becomes big and visible at time $T$ doesn't mean that the cause of that change is proximate and must have happened near $T$, say at $T-1$ or $T-2$.

In complex systems, very faraway causes may create perturbations long after people have forgotten the original cause. And as is for temporal cases, like this example, so it is for spatial cases.

A lesson many managers and pundits have yet to learn.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

The most obvious reason why this is a bad model, from the viewpoint of a manager, is that it doesn't have managerial control variables, which means that if the model were to work, the value of that manager to the company would be nil. It also doesn't work empirically or make sense logically.

Consider the following market share evolution model (which is a very bad model for many reasons, and not one that should be considered for any practical application):

(1) $s[t+1] = 4 s[t] (1-s[t])$

where $s[t]$ is the share at a given time period and $s[t+1]$ is the share in the next period. This is a very bad model for market share evolution, but I can make up a story to back it up, like so:

"When this product's market share increases, there are two forces at work: first, there's imitation (the $s[t]$ part) from those who want to fit it; second there's exclusivity (the $1-s[t]$ part) from those who want to be different from the crowd. Combining these into an equation and adding a scaling factor for shares to be in the 0-1 interval, we get equation (1)."

In younger days I used to tell this story as the set-up and only point out the model's problems after the entire exercise. In case you've missed my mention, this is a very bad model of market share evolution. (See below.)

Using the model in equation (1), and starting from a market share of 75%, we notice that this is an incredibly stable market:

(2) $s[t+1] = 4 \times 0.75 \times 0.25 = 0.75$.

Now, what happens if instead of a market share of 75%, we start with a market share of 75.00000001%? Yes, a $10^{-10}$ precision error. Then the market share evolution is that of this graph (click for bigger):

The point of this graph is not to show that the model is ridiculous, though it does get that point across quickly, but rather to set up the following question:

When did things start to go wrong?

When I run this exercise, about 95% of the students think the answer is somewhere around period 30 (when the big oscillations begin). Then I ask why and they point out the oscillations. But there is no change in the system at period 30; in fact, the system, once primed with $s[1]=0.7500000001$, runs without change.

The problem starts at period 1. Not 30. And the lesson, which about 5% of the class gets right without my having to explain it, is that the fact that a change becomes big and visible at time $T$ doesn't mean that the cause of that change is proximate and must have happened near $T$, say at $T-1$ or $T-2$.

In complex systems, very faraway causes may create perturbations long after people have forgotten the original cause. And as is for temporal cases, like this example, so it is for spatial cases.

A lesson many managers and pundits have yet to learn.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

The most obvious reason why this is a bad model, from the viewpoint of a manager, is that it doesn't have managerial control variables, which means that if the model were to work, the value of that manager to the company would be nil. It also doesn't work empirically or make sense logically.

Labels:

analytics,

change,

management,

marketing,

mathematics

Why asymmetric dominance demonstrates preference inconsistency and spoils market research tools

(Another old CB handout LaTeXed into the blog.)

Recall from the example of ``The Economist'' [in Dan Ariely's Predictably Irrational] that the options to choose from are

$A$: paper-only for 125

$B$: internet only for 65

$C$: paper + internet for 125

When presented with a choice set $\{B,C\}$ about half of the subjects pick $B$; when presented with choice set $\{A,B,C\}$ almost all subjects pick $C$. This presents a logic problem, since if C is better than B then there is no reason why it's not chosen when A is not present; if B is better than C, then there is no reason why C is chosen when A is present.

Logic is not our problem.

The reason we care about ``rational'' models is that they are the foundation of market research tools we like. In particular, we like one called utility. The idea is that we can assign numbers to choice options in a way that these numbers summarize choices (sounds like conjoint analysis, doesn't it?). Once we have these numbers we can decompose them along the dimensions of the options (yep, conjoint analysis!) and use the decomposition to determine trade-offs among products. We denote the number assigned to choice $X$ by $u(X)$.

As long as there is one number * that is assigned to each choice option by itself, we can use utility theory to analyze actual choices and determine what the drivers of customer decisions are. One number per option. Consumers facing a number of options pick that which has the highest number; this is called ``utility maximization,'' is extremely misunderstood by the general public, politicians, and the media, and all it means is that the customers choose the option they like the best, as captured by their consistent choices.

That is the problem.

Suppose we observe $B$ chosen from $\{B,C\}$; then utility theory says $u(B) > u(C)$. But then, if we observe $C$ picked from $\{A,B,C\}$ we have to conclude $u(C) > u(B)$. There are no numbers that can fit both cases at the same time, so there is no utility function. No utility function means no conjoint, no choice model, no market research --- unless we account for asymmetric dominance itself, which requires a lot of technical expertise. And forget about simple trade-off methods.

Meaning what?

Suppose we want to ignore the mathematical impossibility of coming up with a utility function (who cares about economics anyway?) and decide to measure the part-worths by hook or by crook. So we divide the products in their constituent parts, in this case $p$ for paper and $i$ for internet. The options become $\{(p,125), (i,65),(p+i,125)\}$. We can try to make a disaggregate estimation of the part-worths using a conjoint/tradeoff model.

The problem persists.

If $(i,65)$ is chosen over $(p+i,125)$, that means that the part-worth of $p$ is less than 60. That is the conclusion we can get from the choice of $B$ from $\{B,C\}$. If $(p+i,125)$ is chosen over $(i,65)$, that means that the part-worth of $p$ is more than 60. That is the conclusion we can get from the choice of $C$ from $\{A,B,C\}$.

A marketer using these two observations to design an offering cannot determine the part-worth of one of the components: the $p$ part. It's above 60 and under 60 at the same time.

Oops.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

* Up to any increasing transformation of the utility function numbers, if you want to get technical; we don't, and it doesn't matter anyway.

Recall from the example of ``The Economist'' [in Dan Ariely's Predictably Irrational] that the options to choose from are

$A$: paper-only for 125

$B$: internet only for 65

$C$: paper + internet for 125

When presented with a choice set $\{B,C\}$ about half of the subjects pick $B$; when presented with choice set $\{A,B,C\}$ almost all subjects pick $C$. This presents a logic problem, since if C is better than B then there is no reason why it's not chosen when A is not present; if B is better than C, then there is no reason why C is chosen when A is present.

Logic is not our problem.

The reason we care about ``rational'' models is that they are the foundation of market research tools we like. In particular, we like one called utility. The idea is that we can assign numbers to choice options in a way that these numbers summarize choices (sounds like conjoint analysis, doesn't it?). Once we have these numbers we can decompose them along the dimensions of the options (yep, conjoint analysis!) and use the decomposition to determine trade-offs among products. We denote the number assigned to choice $X$ by $u(X)$.

As long as there is one number * that is assigned to each choice option by itself, we can use utility theory to analyze actual choices and determine what the drivers of customer decisions are. One number per option. Consumers facing a number of options pick that which has the highest number; this is called ``utility maximization,'' is extremely misunderstood by the general public, politicians, and the media, and all it means is that the customers choose the option they like the best, as captured by their consistent choices.

That is the problem.

Suppose we observe $B$ chosen from $\{B,C\}$; then utility theory says $u(B) > u(C)$. But then, if we observe $C$ picked from $\{A,B,C\}$ we have to conclude $u(C) > u(B)$. There are no numbers that can fit both cases at the same time, so there is no utility function. No utility function means no conjoint, no choice model, no market research --- unless we account for asymmetric dominance itself, which requires a lot of technical expertise. And forget about simple trade-off methods.

Meaning what?

Suppose we want to ignore the mathematical impossibility of coming up with a utility function (who cares about economics anyway?) and decide to measure the part-worths by hook or by crook. So we divide the products in their constituent parts, in this case $p$ for paper and $i$ for internet. The options become $\{(p,125), (i,65),(p+i,125)\}$. We can try to make a disaggregate estimation of the part-worths using a conjoint/tradeoff model.

The problem persists.

If $(i,65)$ is chosen over $(p+i,125)$, that means that the part-worth of $p$ is less than 60. That is the conclusion we can get from the choice of $B$ from $\{B,C\}$. If $(p+i,125)$ is chosen over $(i,65)$, that means that the part-worth of $p$ is more than 60. That is the conclusion we can get from the choice of $C$ from $\{A,B,C\}$.

A marketer using these two observations to design an offering cannot determine the part-worth of one of the components: the $p$ part. It's above 60 and under 60 at the same time.

Oops.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

* Up to any increasing transformation of the utility function numbers, if you want to get technical; we don't, and it doesn't matter anyway.

Labels:

analytics,

consumer behavior,

marketing

Sunday, January 10, 2010

Evolution of information design in my teaching

People change; books and seminars help.

No, not "empower yourself" books and seminars. Of those I cannot speak. Presentation and teaching books and seminars, that's what I'm talking about. It all starts with this picture (click to enlarge):

I made that picture one evening, as entertainment. I was cleaning up my hard drive and started perusing old teaching materials; noticed the different styles therein; and decided to play around with InDesign. After a while I ended up putting online something that I believe has useful content. It includes some references, which is what I'm writing about here.

Though I'm writing about the references, I cannot overemphasize the importance of the seminars. Tufte's books explain all the material (and the seminar's potential value is realized only after studying the books); but the seminar provides a clear example that it works. Some may read the books and go back to outline-like bullet point disaster slides because they don't trust the approach to work with a live audience. Tufte's seminar allays these fears.

The HBS seminar is more specific to teaching, but for those of us in the knowledge diffusion profession it's full of essential information. There are books on the case method and participant-centered learning, but they are not comparable to the seminar. I know, because I read the books before. And when the seminar started I was skeptical. Very skeptical. And when the seminar ended I reflected on what had happened - the instructor had made us, the audience learn all the material I had read about, without stating anything about it. Reading a book about the classroom skill would be like reading a book about complicated gymnastics.

But, even if one cannot attend these seminars, here are some references that help:

Edward Tufte's books and web site contain the foundations of good information design and presentation.

Made to stick, by the Heath brothers explains why some ideas stay with us while others are forgotten as soon as the presentation is over.

Brain rules, by John Medina, uses neuroscience to give life advice. There are many things in it that apply to teaching and learning; in addition, the skill with which Medina explains the technical material and the underlying science to a popular audience, without dumbing it down, is a teaching/presentation tool to learn (by his example).

Things that make us smart, by Donald Norman, a book about cognitive artifacts, i.e. objects that amplify brain powers. I also recommend his essay responding to Tufte, essentially agreeing with his principles but disagreeing with his position on projected materials.

Speak like Churchill, stand like Lincoln, by James Humes, should be mandatory reading for anyone who ever has to make a public speech. Of any kind. Humes is a speechwriter and public speaker by profession and his book gives out practical advice on both the writing and the delivery. I have read many books on public speaking and this one is in a class of its own.

The non-designer design book, by Robin Williams lets us in on the secrets behind what works visually and what doesn't. It really makes one appreciate the importance of what appears at first to be over-fussy unimportant details.

Tools for teaching, by Barbara Gross Davis covers every element of course design, class design, class management, and evaluation. It is rather focussed on institutional learning (like university courses), but many of the issues, techniques, and checklists are applicable in other instruction environments.

These references helped me (a lot), but they are just the fundamentals. To go beyond them, I recommend:

Donald Norman's other books, as illustrations of how cognitive limitations of people interact with the complexity of all artifacts.

Robin Williams design workshop, which goes beyond the non-designers design book. E.g.: once you understand the difference between legibility (Helvetica) and readability (Times), you can now understand why one is appropriate for chorus slides (H) and the other for long written handouts (T).

Universal principles of design, by William Lidwell, Kritina Holden, and Jill Butler is a quick reference for design issues. I also like to peruse it regularly to get some reminders of design principles. It's organized alphabetically and each principle has a page or two, with examples.

On writing well, by William Zinsser. This book changed the way I write. It may seem orthogonal to presentations and teaching, but consider how much writing is involved in class preparation and creation of supplemental materials.

Designing effective instruction, by Gary Morrison, Steven Ross, and Jerrold Kemp, complements Tools for teaching. While TfT has the underlying model of a class, this book tackles the issues of training and instruction from a professional service point of view. (In short: TfT is geared towards university classes, DEI is geared towards firm-specific Exec-Ed.)

As usual, information in this post is provided only with the guarantee that it worked for me. It may - probably will - work for others. I still stand by the opener of my post on presentations:

Most presentations are terrible, and that's by choice of the presenter.

No, not "empower yourself" books and seminars. Of those I cannot speak. Presentation and teaching books and seminars, that's what I'm talking about. It all starts with this picture (click to enlarge):

I made that picture one evening, as entertainment. I was cleaning up my hard drive and started perusing old teaching materials; noticed the different styles therein; and decided to play around with InDesign. After a while I ended up putting online something that I believe has useful content. It includes some references, which is what I'm writing about here.

Though I'm writing about the references, I cannot overemphasize the importance of the seminars. Tufte's books explain all the material (and the seminar's potential value is realized only after studying the books); but the seminar provides a clear example that it works. Some may read the books and go back to outline-like bullet point disaster slides because they don't trust the approach to work with a live audience. Tufte's seminar allays these fears.

The HBS seminar is more specific to teaching, but for those of us in the knowledge diffusion profession it's full of essential information. There are books on the case method and participant-centered learning, but they are not comparable to the seminar. I know, because I read the books before. And when the seminar started I was skeptical. Very skeptical. And when the seminar ended I reflected on what had happened - the instructor had made us, the audience learn all the material I had read about, without stating anything about it. Reading a book about the classroom skill would be like reading a book about complicated gymnastics.

But, even if one cannot attend these seminars, here are some references that help:

Edward Tufte's books and web site contain the foundations of good information design and presentation.

Made to stick, by the Heath brothers explains why some ideas stay with us while others are forgotten as soon as the presentation is over.

Brain rules, by John Medina, uses neuroscience to give life advice. There are many things in it that apply to teaching and learning; in addition, the skill with which Medina explains the technical material and the underlying science to a popular audience, without dumbing it down, is a teaching/presentation tool to learn (by his example).

Things that make us smart, by Donald Norman, a book about cognitive artifacts, i.e. objects that amplify brain powers. I also recommend his essay responding to Tufte, essentially agreeing with his principles but disagreeing with his position on projected materials.

Speak like Churchill, stand like Lincoln, by James Humes, should be mandatory reading for anyone who ever has to make a public speech. Of any kind. Humes is a speechwriter and public speaker by profession and his book gives out practical advice on both the writing and the delivery. I have read many books on public speaking and this one is in a class of its own.

The non-designer design book, by Robin Williams lets us in on the secrets behind what works visually and what doesn't. It really makes one appreciate the importance of what appears at first to be over-fussy unimportant details.

Tools for teaching, by Barbara Gross Davis covers every element of course design, class design, class management, and evaluation. It is rather focussed on institutional learning (like university courses), but many of the issues, techniques, and checklists are applicable in other instruction environments.

These references helped me (a lot), but they are just the fundamentals. To go beyond them, I recommend:

Donald Norman's other books, as illustrations of how cognitive limitations of people interact with the complexity of all artifacts.

Robin Williams design workshop, which goes beyond the non-designers design book. E.g.: once you understand the difference between legibility (Helvetica) and readability (Times), you can now understand why one is appropriate for chorus slides (H) and the other for long written handouts (T).

Universal principles of design, by William Lidwell, Kritina Holden, and Jill Butler is a quick reference for design issues. I also like to peruse it regularly to get some reminders of design principles. It's organized alphabetically and each principle has a page or two, with examples.

On writing well, by William Zinsser. This book changed the way I write. It may seem orthogonal to presentations and teaching, but consider how much writing is involved in class preparation and creation of supplemental materials.

Designing effective instruction, by Gary Morrison, Steven Ross, and Jerrold Kemp, complements Tools for teaching. While TfT has the underlying model of a class, this book tackles the issues of training and instruction from a professional service point of view. (In short: TfT is geared towards university classes, DEI is geared towards firm-specific Exec-Ed.)

As usual, information in this post is provided only with the guarantee that it worked for me. It may - probably will - work for others. I still stand by the opener of my post on presentations:

Most presentations are terrible, and that's by choice of the presenter.

Labels:

books,

design,

presentations,

teaching

Friday, December 25, 2009

In defense of BS (Business Speak)

Let's leverage some synergies, the comedian said and all laughed.*

This happened in the middle of a technology podcast, the sentence unrelated to anything and off-topic. Such is the state of comedy: make a reference to a disliked group (businesspeople) and all laugh, no need for actual comedic content.

Business-Speak, or BS for short, does have its ridiculous moments. Take the following mission statement:

HumongousCorp's mission is to increase shareholder value by designing and manufacturing products to the utmost standards of excellence, while providing a nurturing environment for our employees to grow and being a responsible member of the communities in which we exist.

There are two big problems with it: First, it wants to be all things to all people; this is not credible. Second, it is completely generic; there's no inkling of what business HumongousCorp is in. Sadly, many companies have mission statements like this nowadays.

Back when we were writing mission statements that were practical business documents, we used them to define the clients, technologies/resources, products, and geographical areas of the business.

FocussedCorp's mission is to to design and manufacture medical and industrial sensors, using our proprietary opto-electronic technology, for inclusion in OEM products, in Germany, the US, and the UK.

This mission statement is about the actual business of FocussedCorp. Mission statements like this were useful: you could understand the business by reading its mission statement. It communicated the strategy of the company to its middle management and contextualized their actions.

FocussedCorp's mission statement is what was then called a strategic square (should be a strategic tesseract): it has four dimensions, client, product, technology/resources, and geography. Which brings up the next point:

Most BS is professional jargon for highly technical material, just like the jargon of other professions and the sciences. So why is it mocked much more often than these others?

Pomposity is a good candidate. Oftentimes managers take simple instructions and drape them in BS to sound more important than they are. In some cases this might even be a form of intimidation, along the lines of "if you question my authority, I'm going to quiz you in this language that you barely speak and I'm fluent in."

Fair enough, but there's much technical jargon in work interactions and only BS gets chosen for mockery. Professionals and scientists do use their long words to the same pompous or intimidating effect as managers, and the comedian in the podcast is as unlikely to know the meaning of "diffeomorphism," "GABA agonist," or "adiabatic process" as that of "leveraging synergies."

I suspect the mockery of BS rather than other professional jargon has to do with the social and financial success of the people who work in business, and therefore are conversant in BS. The mockers are just expressing that old feeling, envy.

They can't play the game, so they hate the players.

------

* Leveraging synergies means to use economies of scope, spillovers, experience effects, network externalities, shared knowledge bases, and other sources of synergy (increasing returns to scope broadly speaking) across different business opportunities.

This happened in the middle of a technology podcast, the sentence unrelated to anything and off-topic. Such is the state of comedy: make a reference to a disliked group (businesspeople) and all laugh, no need for actual comedic content.

Business-Speak, or BS for short, does have its ridiculous moments. Take the following mission statement:

HumongousCorp's mission is to increase shareholder value by designing and manufacturing products to the utmost standards of excellence, while providing a nurturing environment for our employees to grow and being a responsible member of the communities in which we exist.

There are two big problems with it: First, it wants to be all things to all people; this is not credible. Second, it is completely generic; there's no inkling of what business HumongousCorp is in. Sadly, many companies have mission statements like this nowadays.

Back when we were writing mission statements that were practical business documents, we used them to define the clients, technologies/resources, products, and geographical areas of the business.

FocussedCorp's mission is to to design and manufacture medical and industrial sensors, using our proprietary opto-electronic technology, for inclusion in OEM products, in Germany, the US, and the UK.

This mission statement is about the actual business of FocussedCorp. Mission statements like this were useful: you could understand the business by reading its mission statement. It communicated the strategy of the company to its middle management and contextualized their actions.

FocussedCorp's mission statement is what was then called a strategic square (should be a strategic tesseract): it has four dimensions, client, product, technology/resources, and geography. Which brings up the next point:

Most BS is professional jargon for highly technical material, just like the jargon of other professions and the sciences. So why is it mocked much more often than these others?

Pomposity is a good candidate. Oftentimes managers take simple instructions and drape them in BS to sound more important than they are. In some cases this might even be a form of intimidation, along the lines of "if you question my authority, I'm going to quiz you in this language that you barely speak and I'm fluent in."

Fair enough, but there's much technical jargon in work interactions and only BS gets chosen for mockery. Professionals and scientists do use their long words to the same pompous or intimidating effect as managers, and the comedian in the podcast is as unlikely to know the meaning of "diffeomorphism," "GABA agonist," or "adiabatic process" as that of "leveraging synergies."

I suspect the mockery of BS rather than other professional jargon has to do with the social and financial success of the people who work in business, and therefore are conversant in BS. The mockers are just expressing that old feeling, envy.

They can't play the game, so they hate the players.

------

* Leveraging synergies means to use economies of scope, spillovers, experience effects, network externalities, shared knowledge bases, and other sources of synergy (increasing returns to scope broadly speaking) across different business opportunities.

Labels:

business,

BusinessSpeak,

management,

rants

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Online learning can teach us a lot.

Online learning is teaching us a lot. Mostly about reasoning fallacies: of those who like it and of those who don't.

Let us first dispose of what is clearly a strawman argument: no reasonable person believes that watching Stanford computer science lectures on YouTube is the same as being a Stanford CS student. The experience might be similar to watching those lectures in the classroom, especially in large classes with limited interaction, but lectures are a small part of the educational experience.

A rule of thumb for learning technical subjects: it's 1% lecture (if that); 9% studying on your own, which includes reading the textbook, working through the exercises therein, and researching background materials; and 90% solving the problem sets. Yes, studying makes a small contribution to learning compared to applying the material.

Good online course materials help because they select and organize topics for the students. By checking what they teach at Stanford CS, a student in Lagutrop (a fictional country) can bypass his country's terrible education system and figure out what to study by himself.

Textbooks may be expensive, but that's changing too: some authors are posting comprehensive notes and even their textbooks. Also, Lagutropian students may access certain libraries in other countries, which accidentally on purpose make their online textbooks freely accessible. And there's something called, I think, deluge? Barrage? Outpouring? Apparently you can find textbooks in there. Kids these days!

CS has a vibrant online community of practitioners and hackers willing to help you realize the errors of your "problem sets," which are in fact parts of open software development. So, for a student who wants to learn programming in Python there's a repository of broad and deep knowledge, guidance from universities, discussion forums and support groups, plenty of exercises to be done. All for free. (These things exist in varying degrees depending on the person's chosen field -- at least for now.)

And, by working hard and creating things, a Lagutropian student shows his ability to prospective employers, clients, and post-graduate institutions in a better country, hence bypassing the certification step of going to a good school. As long as the student has motivation and ability, the online learning environment presents many opportunities.

But herein lies the problem! Our hypothetical Lagutropian student is highly self-motivated, with a desire to learn and a love of the field. This does not describe the totality of college students. (On an related statistical note, Mickey D's has served more than 50 hamburgers.)

The Dean of Old Mizzou's journalism school noticed that students who downloaded (and presumably listened to) podcasts of lectures retained almost twice as much as students in the same classes who did not download the lectures. As a result, he decreed that henceforth all journalism students at Old Mizzou would be required to get an iPod, iPhone, or similar device for school use.

Can you say "ignoring the selection effect"?

Students who download lectures are different from those who don't: they choose to listen to the lectures on their iPod. Choose. A verb that indicates motivation to do something. No technology can make up for unmotivated students. (Motivating students is part of education, and academics disagree over how said motivation should arise. N.B.: "education" is not just educators.)

Certainly a few students who didn't download lectures wanted to but didn't own iPods; those will benefit from the policy. (Making an iPod required means that cash-strapped students may use financial aid monies to buy it.) The others chose not to download the lectures; requiring they have an iPod (which most own anyway) is unlikely to change their lecture retention.

This iPod case scales to most new technology initiatives in education: administrators see some people using a technology to enhance learning, attribute that enhanced learning to the technology, and make policies to generalize its use. All the while failing to consider that the learning enhancement resulted from the interaction between the technology and the self-selected people.

This is not to say that there aren't significant gains to be made with judicious use of information technologies in education. But in the end learning doesn't happen on the iPod, on YouTube, on Twitter, on Internet forums, or even in the classroom.

Learning happens inside the learner's head; technology may add opportunities, but, by itself, doesn't change abilities or motivations.

Labels:

quantThoughts,

rants,

teaching,

technology

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)