Rotten Tomatoes and Batwoman

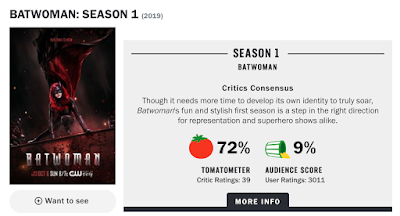

The day after the pilot, a familiar pattern emerges:

Using the same math as these two previous posts, it's 198,134,550 (almost 200 million) times more likely that the critics are using the opposite criteria to those of the audience than they both using the same criteria.

A couple of days later, more data is available:

And today (with a tip of the Homburg to local vlogging nerd Nerdrotics), it's even worse:

With this data (ah, the joys of reusable models, even if "model" is a bit of a stretch for something so simple, relatively speaking) we get that it's now 11,028,450,795,963,200 (eleven quadrillion!) times more likely that the critics are using the opposite criteria to those of the audience than they both using the same criteria.

For what it's worth, I liked the pilot, despite my nit-picking it on twitter:

Aerobics: The Paper that Started The Craze.

Here are three explanations that all match the data:

I. The official story: running develops cardiovascular endurance. This is the story that led to the aerobics explosion, to jogging, and to all sorts of "cardio" nonsense. Note that this story is isomorphic to "playing basketball makes people taller."

II. The selection effect story: people with good cardiovascular systems can run faster than those without. This is the "tall people are better at basketball than short people" version of the story.

III. The athletes are better at both story: people who have athletic builds (strong muscles, large thoracic capacity, low body fat) are better at both running and cardiovascular fitness because of that athleticism.

Most likely the result is a combination of these three effects, or in expensive words, the three variables (cardiovascular fitness, muscular development, and running ability) are jointly endogenous. Note also the big excerpt from Body By Science at the end of this post.

Let's take a closer look at that table:

Not that I'm questioning Cooper's data (okay, I am), but isn't it strange that there are no cases when, say a runner with a distance of 1.27 mi had VO2max of 33.6? That the discrete categories on one side map into non-overlapping categories on the other? No boundary errors? That's an unlikely scenario.

Also, no data about the distribution of the 115 research subjects over the five categories. That would be interesting to know, since the bins for the distance categories are clearly selected at fixed distance intervals, not as representatives of the distribution of subjects. (It would be extremely suspicious if the same number of subjects happened to fall into each category. But if they don't, that's informative and important to the interpretation of the data.)

I know this was the 60s; on the other hand, the 60s were the first real golden age of large-scale data processing (with those "computer" things) and a market research explosion.

One of the factors that confounds these "cardio" results is that training for a specific test makes you better at that test. Another is that strengthening the muscles that are used in a specific motion makes that motion less demanding and therefore puts less strain on the cardiovascular system.

This excerpt from Body By Science illustrates both of these confounds:

Grant Sanderson (3 Blue 1 Brown) on prime number spirals

A late addition: Elon Musk promises PowerPacks for CA

Which brings up two thoughts:

a. Is "just waiting on permits" the new "funding secured"?

b. Each powerpack has 210 kWh capacity, so one charges ~3 Teslas, assuming they're low on charge but not zero. (Typical tank truck ~ 11,000 gal tops-up 733 x 15 gal gas tanks. Just FYI)