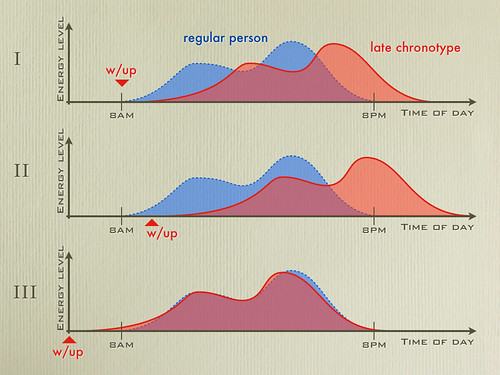

A late chronotype is someone whose energy level, after waking up, increases more slowly than than the average person's; also known as "not a morning person." Typically this slow start is balanced by high levels of energy in the evening, when other people are crashing. (Panel I below depicts this for illustration.)

Many late chronotypes believe that the solution to their problem is to sleep late. That is exactly the wrong approach. The problem of being a late chronotype is that our level of energy doesn't match everyone else's. Starting the day later only increases the problem (as illustrated in panel II).

The solution, which may sound counter-intuitive, is to get up much earlier than everyone else, therefore reaching peak energy at the same time as everyone else (as shown in panel III).

I have used a number of approaches to manage being a late chronotype (caffeine, no breakfast, exercise, ice-cold morning shower), but none was ever as effective as being on Boston time while living in California.